My initial attempts to learn programming start with not starting: My father encouraged me to learn to programming when I was 14. But he suggested QBasic and TurboPascal. I think his idea was that I would start with QBasic and then "graduate" to Pascal. I tried to learn QBasic a bit based on a book that walked one through developing a address database. However, this was not very motivating for me: The QBasic programs could not be started directly, but needed to be loaded in an editor before. Aside of that, I did not use an address database and even then there were plenty on freeware CDs that came with computer magazines. And these were “real” Windows applications!

HTML and CSS

I loved graphic design and 3D Modeling and other, more artistic uses of computers. So I guess the ability to do something visual and interactive was appealing about HTML and CSS.

Looking at my old files, it must have been 2005 or so when I learned to create websites in CSS and HTML. I don't know what motivated me. Maybe it was related to my interest in graphic design combined with a bit of background knowledge about web development that I picked up in computer magazines that my father read.

One source for learning was a brochure on HTML and CSS, a bit under 100 pages, I guess 1. The booklet showed how to create a simple website in HTML and CSS. However, I must have learned some HTML before. I remember since after working through the tutorial I did rebuild a website I created previously. It was using invisible tables before and I made it work with CSS alone as the booklet and some articles informed me that invisible table layouts are bad. At this time, using CSS only for layout was somewhat new and needed to be established so a lot of work of people went into telling others that they should stop using table based layouts. They convinced me, as you see.

Another source was the Website SelfHTML. It was like the German MDN, but I guess MDN did not exist at that time. It listed HTML elements, CSS and Javascript keywords, together with compatibility to different browsers and some usage examples. It was popular, well usable and it was available not only on the web but also as a zip file, so it could be read without internet access.

In 2006 I designed and developed a website during a 3 week internship. It was all manually coded as the company did not want to run a CMS and static site generators not existing yet or me not knowing about them.

Learning JavaScript

I guess the work on Websites also exposed me to JavaScript. Some other factors might have been that

- I could have read about it in computer magazines

- my dad had a knowware-booklet on JavaScript, probably teaching the style that one used and wrote JavaScript in the late 90s – to implement some gimmicks on websites. I can’t remember using it, though.

- SelfHTML also had a section on JavaScript, just a click away.

- A friend of mine was using it at the time. I don't know exactly what for, but I remember that he tried to implement a rudimentary "canvas" made from 1px wide HTML elements; one could then control these pixel-like elements.

- At some point I watched some videos from YouTube on "JavaScript – the good parts" by Douglas Crockford and watched them. We did not have fast internet in our home, so I downloaded them and burned them on a CD (I guess this was about 2007?) . I guess they did not translate into practically useful knowledge directly, but later gave me some confidence to defend my choice of language against obnoxious nerds who claimed that it was ‘not a real programming language’.

In 2007 I made my first (surviving) attempts to write in JavaScript, a game that I seem to have copied from somewhere. It generated a random number and asked the player to guess it, hinting if the number guessed was right or needs to be higher or lower.

In 2009 I try again by reading Javascript – the Definitive Guide. I tried to make sense of what is written in the book (I have the tendency to motivate myself, too, by reading books cover to cover, even if they are more meant to be reference works).

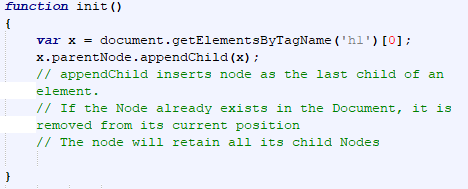

I have copied code from the book to try it out; a lot seems to be on how functions and method work, which is also one of the unusual (or rather functional-paradigm.-oriented) aspects of JavaScript.

A month later I order "ppk on JavaScript". This I remember as the book that made JavaScript "click" for me.

It seems I improved on organizing my recreations of code examples and added the page numbers to the file name. There are also more code I tried – over 60 snippets are in that folder

I also wrote my own comments in the examples, some with minor grammar or spelling mistakes – my native language is German, but as all instruction was English I kept writing comments in English.

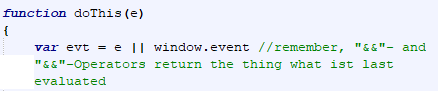

The example with var evt = e || window.event also shows one of the disadvantages of learning JavaScript at this point of time: The browser implementations varied, so one needed to check which of two possible implementations of e.g. the event existed (here, it was either a parameter or attached to the globally accessible window)

Here some retrospective praise for what I assume made this book so helpful for me:

- The book combines real-life, worked examples and explanation of the code used for them. So the chapter describing a small webapp with code for event handling also explained how the browser handles events.

- It has well made diagrams instead of trying to explain the DOM in text only

I remember some things that were confusing me as a beginner:

- That there is a big difference between

"hello"andhello, one being a string that contains text, the other being a variable which can contain anything. Confusingly, the thing that was just what I saw on the screen, the letters, needed to be specially marked by""whereas the words doing magic variable stuff did not require any special markers. - There is also a big difference between

doThisanddoThis()one being just a variable (which can contain a function) and the other the function told to execute by the attached() - Events were confusing! (At least until I read “ppk…”). Events are a concept that allows to react to user input, e.g. clicks and typing.

- A function that "handles" an event gets a event-parameter. Somehow that event parameter appeared magically: Whenever I clicked on an element to which I assigned a handler function, that function got called and in the function I could use a parameter that held information on where I clicked exactly and other details. WHAT MADE IT APPEAR?! I was baffled 2.

- Events “bubbled”, that meant they occurred on the element that I clicked directly but also on the elements that this element is in (imagine boxes in boxes).

I continued using JavaScript ever since, learned frameworks like backbone and later vue.js and now play a bit with TypeScript. However, I think that it got harder to learn JavaScript today: Every 'serious' project today uses some sort of library which means you need webpack and npm and node and whatnot. This makes learning hard and the tools you need to wield rather unwieldy for a beginner 4. Today I would probably start with Python, I guess: Its usage demands less use of frameworks and libraries (though they certainly exist).

“Teaching yourself programming” as a genre (with problems)

Above story falls somewhat into a typical genre of personal lore of people in IT: “I taught myself X”. Professor of Computer Science Felienne Hermans has written about the problems of the “taught myself programming”-story on her blog: I am going to stop saying I taught myself programming when I was 10 and maybe you should too – and what I describe above falls (potentially) in this genre. Like Felienne, I want to point out that what I learned was not just “What I did” but also the context I happen(ed) to live in:

- Obviously my father being interested in computer programming and having magazines, booklets and books on it supported and legitimized my learning

- I had my own computer.

- I obviously drew from the work of many authors and teachers, although most of it was via some medium rather than direct teaching

- I had a least one friend who was also interested in programming

You could say that the first two points made it possible to get started with the learning and the two latter points made the activity itself somewhat meaningful to me. I never met the authors of the books, but they still were part of an ‘imagined community’ of people interested in similar things. Most importantly, having a friend being also interested in programming was a strong factor as I could talk with him about what I learned or learn from him what he did and follow that up (and thus create a topic to talk about more.)

To not leave you without further things to read, I want to point to some academic writings on the claims of being “self-taught”. In some communities being self taught is very important – and it can mean multiple things. One is the rejection of formal education, which can be often found in hacker culture 3. However, this is not constrained to classic “hacker” activities. Perkel and Herr-Stephenson research in an online arts community and describe : “…that using tutorials, even when a part of a seemingly self-motivated, “informal” learning, can be positioned in opposition to being self-taught” as they are not learning without help and on-ones-own 8. Lange describes how kids use and produce content for YouTube and finds that kids she talked to often downplayed the “social sources of support and direct assistance they received” (p.189) 6

This tendencies fit larger patterns of silicon-valley culture: Individuals, not groups or their institutions, are seen to drive change, free of hierarchies (see e.g. p38 in Turner, 2006 9) and charismatic technology enables self directed learning and tinkering (much like the technology’s creators prefer see themselves) 5.

Notes:

- Change 2021-03-02: In the intro I wrote that I did (not) learn “Quick Basic” (I changed that now) but that it did not create programs you could easily run. Turns out Quick Basic could do that. What I used, however, was QBasic, a limited derivative of QuickBasic which came with any Windows until Windows 2000. You can try QBasic at the Internet Archive.

- 2021-04-01: I found an old DVD with recordings of Douglas Crockford talks that I downloaded from YouTube in May 2009, as well as some accompanying slidedecks (The videos are The JavaScript Programming Language, Quality, The good parts, DOM Theory and Advanced JavaScript. I don't know why I put them on DVD, possibly I did not have web access in my room yet.

-

The publisher had a lot on different computer topics and they are still around. ↩

-

Years later I learned about the publish-subscribe-pattern that does this. ↩

-

E.g. in Levy, 2010 7, p. 7 “There were enough obstacles to learning already—why bother with stupid things like brown-nosing teachers and striving for grades?”, p 184: “Years of working in the free-flow world of electronics had infused Marsh with the Hacker Ethic, and he saw school as an inefficient, repressive system. Even when he worked at a radical school with an open classroom, he thought it was a sham, still a jail.” ↩

-

Others wrote about the problems of the JavaScript infrastructure for learners, too, see e.g. Rachel Andrews’ HTML, CSS and our vanishing industry entry points. Kate Compton however points out that “…all of this is optional” and that you still can get by with “a lil html file”. ↩

-

Ames, Morgan G. „Charismatic Technology“. Aarhus Series on Human Centered Computing 1, Nr. 1 (5. Oktober 2015): 12. https://doi.org/10.7146/aahcc.v1i1.21199. ↩

-

Lange, Patricia G. Kids on YouTube: Technical identities and digital literacies. Left Coast Press, 2014. ↩

-

Levy, Steven. Hackers. 1st ed. Sebastopol, CA: O’Reilly Media, 2010. ↩

-

Perkel, Dan, und Becky Herr-Stephenson. „Peer pedagogy in an interest-driven community: the practices and problems of online tutorials“, 2008. ↩

-

Turner, Fred. From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism. 1 edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006. ↩